Since I also watch television – including seeing a number of blockbuster movies released direct to streaming during the pandemic – I figured I would expand this blog to include some non-cinematic visual media. I call it TV Corner.

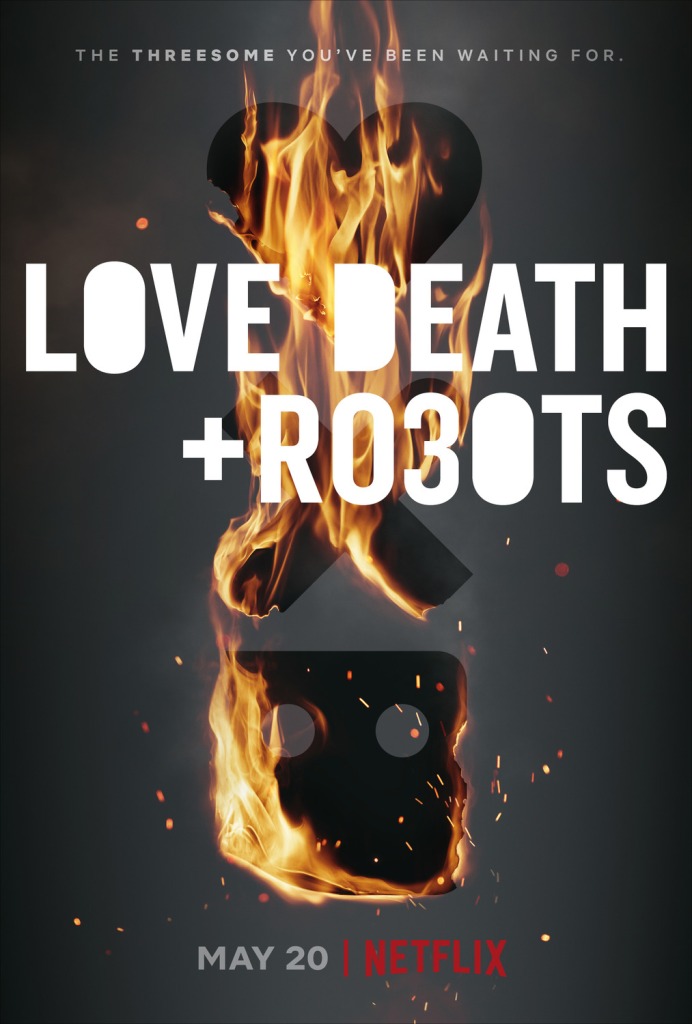

Love, Death + Robots is a reinvention of the portmanteau movie format – a form that has produced such varied works as Dead of Night (1945), Dr Terror’s House of Horrors (1965), The Company of Wolves (1984), Tale of Tales (2015) and The Ballad of Buster Scruggs (2018) – for the streaming age.

LD+R is a series of animated science fiction and horror shorts, released in (so far) three ‘volumes’ on Netflix and aimed at a mature audience. It was originally envisioned by creators David Fincher (The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo) and Tim Miller (Deadpool) as a reboot of the 1981 film Heavy Metal, itself an anthology of adult animation based on the SF magazine of the same name, featuring violence, sexual material and profanity. Met with mixed reviews, to which I cannot add as I have never seen it, at best it was hailed as a revolutionary proof that animation could be for grown ups, and at worst decried as charmless, adolescent and cruel.

In 2008, long before Deadpool, with Fincher riding high on the cult success of Fight Club and Miller running an animation studio, the pair began shopping the idea of a Heavy Metal reboot around. The pitch was to produce an R-rated animated feature adapting several stories from the original magazine, just like the 1981 offering, but presumably with a deifferent selection of stories. Miller’s Blur studio would provide the animation, with Fincher, Miller and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles creator Kevin Eastman all pegged to direct segments of the anthology. Paramount signed on, but funding was elusive. Then Robert Rodriguez (El Mariachi) acquired the rights to Heavy Metal, something that the team had either neglected to do or to renew, with the intention of creating his own anthology project which also never materialised.

In the the age of superhero blockbusters, portmanteau cinema was apparently dead.

And then Netflix came along, and offered a unique opportunity. Two filmmakers with cult credibility and an edgy concept was just what the distributor was looking for. In the absence of a good, old-fashioned transphobic comedy set or a documentary about a whack-job with bad hair and a menagerie of mistreated moggies, they were willing to orderthe project, not as a portmanteau movie, but as a set of short films with the one thing no network television distributor could give them: no fixed episode length.

And so came Love, Death + Robots, a series of eighteen animated shorts, ranging in length from 6 to 17 minutes. Sixteen were based on existing short stories, the other two were original, with the only official criterion being that the story should include one or more of love, death and robots. A second ‘volume’ in 2021 added eight more shorts, and a third in 2022 another nine, with the longest single installment pushing out to twenty-one minutes.

The bulk of the episodes have screenplays by Philip Gellat, based on short stories by a wide range of authors, with two original entries and a few adaptations by other screenwriters. A wide array of directors took on episodes, many of them first timers with experience in animation and visual effects. The look, feel, themes and approaches of the films varied wildly, as you would hope from an anthology.

Volume 1

Three Robots

Adapted by Philip Gellat (Europa Report) from a short story by John Scalzi (Old Man’s War), directed by Victor Maldonado and Alfredo Torres

A trio of robots explore the ruins of human civilisation, speculating on the causes of their creators’ extinction.

Although a little morbid, this opener (in some running orders; Netflix appears to randomly select one of a small number of orders for each user,) is relatively light and humourous, while still having something to say about the self-destructive nature of humanity.

Beyond the Aquila Rift

Adapted by Philip Gellat from a short story by Alastair Reynolds (Revelation Space), directed by Léon Bérelle, Dominique Boidin, Rémi Kozyra, Maxime Luère

Passing through a superlight accelerator, a spaceship is flung off-course and winds up at a remote station where the captain’s ex recovers them.

This episode shifts gears, throwing graphic sex, champagne-drenched breasts and some serious body-horror into a story of either cosmic horror or universal compassion, depending which way you look at it. I think it’s supposed to be the latter, but there are just a few inconsistencies that make me wonder. The point might be clearer if less of the relatively oppulent runtime was taken up by the sex scenes, but on the plus side it avoids the ingrained misogyny and sexual or sexualised violence – perhaps the legacy of Heavy Metal – that looms over many of the other episodes.

Ice Age

Adapted by Philip Gellat from a short story by Michael Swanwick (The Iron Dragon’s Daughter), directed by Tim Miller

A young couple – Mary Elizabeth Winstead (Birds of Prey) and Topher Grace (Spider-Man 3) in what I think are the only live-action performances in the series, although some of the motion-capture animation is photo-real enough to make me wonder – discover a tiny civilisation in the antique freezer in their new home. Over the course of hours they watch this microcosm rise from hunter-gathering to post-industrial, to near-destruction and eventual singularity, before seeing another world begin.

Switching back to a lighter mode – although technically encompassing the horrors of nuclear war – Ice Age considers cycles of life and death and the nature of perspective.

Sonnie’s Edge

Adapted by Philip Gellat from a short story by Peter F Hamilton (Mindstar Rising), directed by Dave Wilson

Sonnie is one of the best Beastie fighters there is, using her mind to control a genetically-engineered monster in gladiatorial battles. They say that her edge is her rage against the men who raped her, but is there more beneath the surface?

And once more coming close to full edgelord mode, Love, Death + Robots brings us what appears to be a deconstruction of misogynist assumptions and rape-as-backstory so on the nose that it is almost indistinguishable from the thing it is deconstructing, bar a couple of explicit declarations. There is a lot of sexist and misogynist language in this one, and putting that in the mouths of ‘the bad guys’ only covers so many sins, and some jarringly sexualised violence. There are some stories that manage to walk a fine line between really stupid and really clever. ‘Sonnie’s Edge’ contains a huge amount that is nasty in service of deconstructing the same tropes, but I think in the end it works.

When the Yoghurt Took Over

Adapted by Janis Robertson from a short story by John Scalzi (available online,) directed by Victor Maldonado and Alfredo Torres

A genetically modified fermenting bacteria results in the emergence of a hyper-intelligent strain of yoghurt that takes over the world and ushers in a form of utopia, but are they doing it for humanity’s good or their own?

The second of John Scalzi’s three offerings in this volume is another piece of pointed whimsy, as humanity screw up the yoghurt’s ‘soft touch’ attempt to save them with such predictability that you have to wonder if it was the plan all along.

The Secret War

Adapted by Philip Gellat from a short story by David W Amendola, directed by István Zorkóczy

A Red Army unit in WWII hunts for the undead in Siberia. Spread thin, a platoon of soldiers discover the horrifying source of the infestation, only to face a massive warren of ghouls in what they know must be a last stand.

Probably the most sombre of the several military pieces offered by the series, The Secret War gives us an amplified picture of men – and they are all men, and call it realism but it is notable after the last five entries that this one has no female characters at all – facing the dark secrets of their own cause.

Sucker of Souls

Adapted by Philip Gellat from a short story by Kirsten Cross, directed by Owen Sullivan

A group of mercenaries and their academic employer find themselves pursued when the occupant of the tomb the professor is excavating turns out to be significantly more a) active and b) Dracula than expected.

A radical stylistic departure from the preceding episodes, with a hand-drawn look in place of the hyper-realism of Three Robots, Beyond the Aquila Rift, Sonnie’s Edge and The Secret Wars, or the clean whimsical lines of Ice Age or The Day the Yoghurt Took Over. It also eschews gratuitous boobies in favour of some wince-inducing vampire dong trauma. The soldierly banter is, perhaps authentically, crude, but the action has a brutal, splattery… I don’t know if charm is the word, but there’s something.

The Witness

Screenplay and original story by Alberto Mielgo (The Windshield Wiper), directed by Alberto Mielgo

A woman witnesses the murder of a woman who looks just like her in a window across from hers. She flees the killer across the city, but ultimately races to a fatal conflict in which she kills her pursuer, only to realise that she has been seen by a man who looks just like the man she just killed.

Frenetic, noisy and gratuitously sexualised – the female leads spends the entire pursuit in a state of undress and allows herself to be pushed into her work as an exotic dancer even while fearing for her life, dancing for an extended scene while her pursuer watches from a couch full of leather-clad gimps – the film is animated using motion capture that is barely distinguishable from live action (at least on my screen.) This is one of the very few episodes not drawing from an existing story, and while boldly styled it comes off as a bit of a mess.

Suits

Adapted by Philip Gellat from a short story by Steven Lewis, directed by Franck Balson

The ranchers working a cluster of farms mount their heavily-armed exosuits to battle encroaching ‘deebees,’ but who is the real invader here?

Opening as a simple tale of brave American frontiersmen – and women, although overall the ladies are shown holding the doors and defending the children rather than riding out to the front line – defeating a voiceless, savage enemy, the ending of the film subverts that theme in an explicit comment on colonialism.

Good Hunting

Adapted by Philip Gellat from a short story (available online in two parts) by Ken Liu (The Grace of Kings), directed by Oliver Thomas

The young son of a demon hunter grows up questioning his father’s calling through his friendship with a fox spirit. As the English bind China with steel rails and steampunk technology, the fox loses her magic, scraping a living from her body until an appalling violation leads her to seek her old friend’s help in finding a new kind of magic.

While the fox spirit ultimately becomes her own avenger, she is another female character in this collection ultimately defined by violation. While her sex work is not inherently shameful, her ultimate transformation is catalysed by an act of forced sexual and surgical abuse, and even her friendship with the mechanic begins at the moment of her mother’s violent murder for daring to arouse a man’s interest. On the other hand, this is one of the few entries to move away from a western point of view.

The Dump

Adapted by Philip Gellat from a short story by Joe Lansdale (Bubba Ho-Tep), directed by Javier Recio Gracia

A city inspector tries to get an old man to leave the dump where he lives. The old man tells a tale of his late friend and the monster that ate him.

Of al the shorts in this volume, this one has stayed with me the least. There are no likeable characters, and I didn’t find the story at all compelling. As a class or culture clash it fails because everybody is horrible.

Shape-Shifters

Adapted by Philip Gellat from a short story by Marko Kloos (Terms of Enlistment), directed by Gabriele Pennacchioli

A pair of werewolves are deployed with the USMC in Afghanistan. Despised by their comrades and commanders, but brutally effective, their value is questioned after an attack by a Taliban werewolf which leaves one of them dead, along with an entire garrison, and the other at odds with command over the hunt for the killers.

Once more, the modern military setting brings with it both a lack of female characters and a welter of misogynist banter that the story could honestly do without. The story itself is okay, but doesn’t feel hugely fresh.

Fish Night

Adapted by Philip Gellat from a short story by Joe Lansdale (available online,) directed by Damian Nenow

Two travelling salesmen are trapped in the desert by a burst tyre. At night, the ghosts of the ocean come.

Like Lansdale’s other entry, this is essentially a two-hander which does more pondering that point making, with its ultimate theme seemingly that it’s better to be an introspective old fart than to have any genuine spiritual curiosity.

Helping Hand

Adapted by Philip Gellat from a short story by Claudine Griggs (available online,) directed by John Yeo

An astronaut carrying out maintenance in space is knocked from her handholds. With no other means of moving herself in space and no hope of rescue, she is forced to take desperate measures for her own salvation.

This one is pretty much a solo show, with a female lead who is neither sexualised nor victimised. The astronaut is tough, professional and resourceful and the drama entirely drawn from her immediate situation. It is perhaps no coincidence that this is the only episode of the entire series originally written by a woman.

Alternate Histories

Adapted by Philip Gellat from a short story by John Scalzi (available online,) directed by Victor Maldonado & Alfredo Torres

A sophisticated system displays alternate histories created by a range of scenarios surrounding the premature death of Hitler.

Scalzi’s third offering is a weird piece of fluff, playing out sketches of what if scenarios branching out from various deaths of Hitler in 1908 Vienna, including mugging, bratwurst cart accident and time-travel sex marathon (a fate which makes much more sense if you think of the system as a publically accessible search engine with an autofill feature.) While most of the films in the series are lovingly crafted, this feels almost like an afterthought, a throwaway.

Lucky 13

Adapted by Philip Gellat from a short story by Marko Kloos, directed by Jerome Chen

A rookie pilot is assigned to the ironically named dropship ‘Lucky 13.’ The ship has survived the loss of two other crews, but protects her new pilot unfailingly, bringing her crew and troops through the worst possible situations unscathed, until one last flight when she gives all she has to give.

‘Lucky 13’ just goes to prove that you can have a military SF story with a female lead and not resort to sexist banter, misogynist insults or gratuitous boobs. Who even knew? It’s a simple reflection on the bond between the pilot and the craft that is the centre of her professional life, peppered with some brilliantly realised and pathos-laden SF battle sequences.

Blindspot

Screenplay and story by Vitaliy Shushko, directed by Vitaliy Shushko

A team of cybernetic criminals try to rob an armoured convoy in the titular surveillance gap. The job turns deadly when a massive security robot takes a hand, but the team may have prepared for even the worst eventuality.

The second original offering is pretty basic fare, but then again sometimes you’re in the mood for the old protein and carb combo. Once again, it slips in a little casual misogyny – a heist is no more a place for sexual harrassment than any other workplace – but is overall a fairly fun bit of nonsense. It does lose points for the ending, which is only a few settings above ‘it was all a training exercise.’

Zima Blue

Adapted by Philip Gellat from a short story by Alastair Reynolds, directed by Robert Valley

A journalist is granted an interview with a reclusive artist. He gives her his full life story on the eve of his final artwork, but the story is not what she expects, and the final work is something nobody is prepared for.

A musing on art and consciousness, ‘Zima Blue’ s reminiscent of some of Aasimov’s Robots novels. A gentle, almost meditative piece in stark contrast to many of the more action packed installments, it makes a thoughtful bookend to the Volume.

My Final Thoughts

Despite a broad mix of stories, volume 1 suffers from a few recurrent problems, most of which – heavy use of misogynist insults, sexualised violence and crude banter – seem to stem from the series’ desire to be edgy. Many of the films seem heavily influenced by the fact that the makers were permitted, perhaps encouraged, to include as much nudity (mostly, but not exclusively, female) and sex as they liked. I’m curious how much of this can be attributed to the screenwriting of Philip Gelatt (or possibly to the brief that he was given.) To find out, I will probably pick up a copy of the anthology collecting the short stories and two original screenplays at some point: Love, Death + Robots: The Official Anthology: Volume One.

Problems aside, there’s enough to like that most viewers can find something to tickle their fancy, and the series was successful enough to invest in the two shorter succeeding volumes, which I will discuss in a future article.

Season 1 was great! I have yet to see any more.